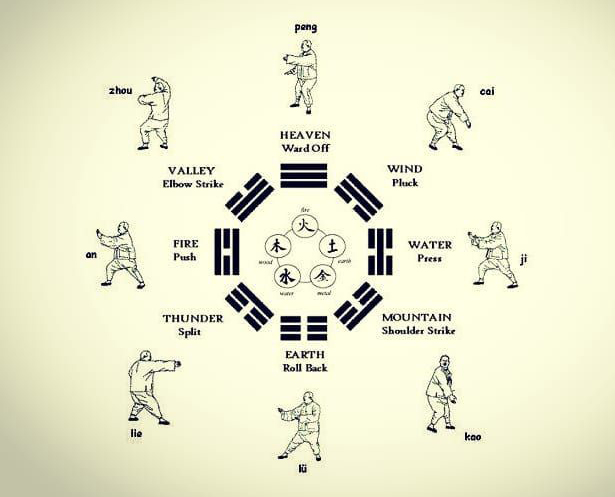

The Thirteen Postures of Tai Chi (十三勢, Shí Sān Shì) form the foundation of Tai Chi practice. These postures, or energies, combine basic movements and principles of the art, integrating footwork, hand techniques, and body alignment. These postures are divided into eight basic hand techniques (八法, Ba Fa) and five footwork directions (五步, Wu Bu). Together, they represent the core movements and energies of Tai Chi.

The Eight Energies (Bā Fā / 八法) – Hand and Arm Techniques

The Eight Energies (or Eight Forces) are the core movements that define how energy is issued, absorbed, and redirected in Tai Chi. They are essential for both internal energy cultivation and martial applications. These energies are often divided into two groups:

- Four Primary Energies (四正 / Sì Zhèng) – Fundamental and commonly used techniques.

- Four Secondary Energies (四隅 / Sì Yú) – More advanced techniques for breaking balance and attacking from different angles.

The Four Primary Energies (四正 / Sì Zhèng)

These are the foundation of Tai Chi movements and are used in Grasp the Bird’s Tail, one of the most fundamental sequences in Tai Chi forms.

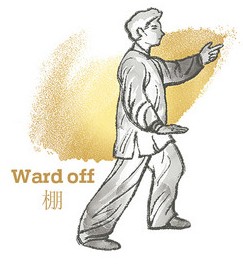

1. Peng (掤) – Ward Off

- Direction: Expanding outward, like an inflated balloon.

- Feeling: Buoyant, resilient, and structure-based rather than muscular force.

- Application:

- Used to deflect an incoming force without clashing.

- Helps maintain postural integrity and prevent collapsing when pushed.

- Example: In Push Hands, if someone pushes your chest, you expand outward slightly to neutralize their force.

- Example in Forms: Found in movements like "Grasp the Bird’s Tail" and "Single Whip."

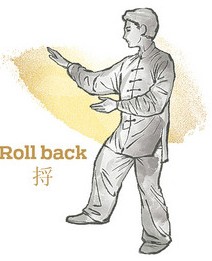

2. Lu (捋) – Roll Back

- Direction: Absorbing and guiding force to the side or rear.

- Feeling: Like water flowing around an obstacle.

- Application:

- Used to redirect an opponent’s energy, making them lose balance.

- Often follows Peng—first absorb (Peng), then guide force away (Lu).

- Example: If an opponent pushes your shoulder, instead of resisting, you roll back and let them fall forward.

- Example in Forms: Present in "Grasp the Bird’s Tail" sequence.

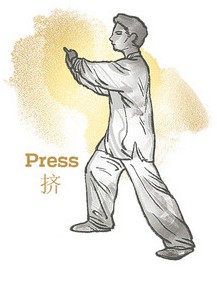

3. Ji (擠) – Press

- Direction: Forward compression, like squeezing water through a hose.

- Feeling: Compact and focused power delivered with both hands.

- Application:

- Used to apply concentrated force to an opponent’s center.

- Often follows Lu—first absorb the attack, then counter with Ji.

- Example: If an opponent leans forward after their force is redirected, you use Ji to press them further off balance.

- Example in Forms: Found in "Grasp the Bird’s Tail" after Lu.

4. An (按) – Push

- Direction: Downward and outward pressure, like a sinking wave.

- Feeling: Rooted and relaxed rather than a hard shove.

- Application:

- Used to press an opponent downward before issuing force outward.

- Often follows Ji—first press in (Ji), then sink and expand force downward (An).

- Example: If an opponent is already slightly off balance, An can completely uproot them.

- Example in Forms: The last movement of "Grasp the Bird’s Tail."

The Four Secondary Energies (四隅 / Sì Yú)

These energies complement the primary four and introduce more complex techniques.

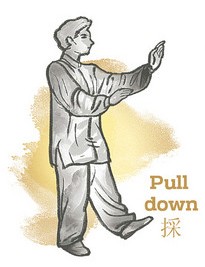

5. Cai (採) – Pluck / Pull Down

- Direction: Quick downward pull, like picking fruit from a tree.

- Feeling: A sharp, snatching movement designed to break an opponent’s structure.

- Application:

- Used to unbalance an opponent by pulling their limb suddenly.

- Often follows a grab—once contact is made, apply Cai to jerk them off balance.

- Example: If someone grabs your wrist, you can use Cai to yank their arm downward and disrupt their stance.

- Example in Forms: Seen in "Grasp the Bird’s Tail" and "Step Back and Repulse Monkey."

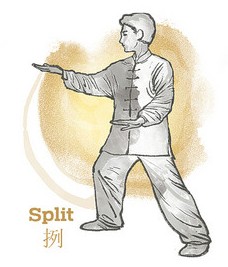

6. Lie (挒) – Split

- Direction: Opposing forces moving in different directions.

- Feeling: A shearing or twisting force, like wringing out a towel.

- Application:

- Used to break an opponent’s structure through separation of forces.

- Effective for joint locks and throws.

- Example: If someone grabs your wrist, you can use Lie to twist their arm in opposite directions, leading to a lock or throw.

- Example in Forms: Found in "Diagonal Flying."

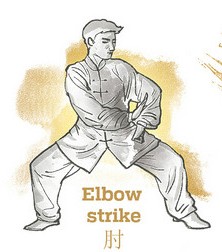

7. Zhou (肘) – Elbow Strike

- Direction: Short-range explosive force using the elbow.

- Feeling: Compact and powerful, ideal for close-quarters combat.

- Application:

- Used when an opponent is too close for extended arm techniques.

- Can be used for striking or applying leverage.

- Example: If an opponent gets too close while grappling, a quick elbow strike (Zhou) can create space.

- Example in Forms: Found in "Elbow Strike" and "Step Forward to Deflect, Parry, and Punch."

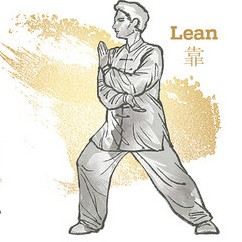

8. Kao (靠) – Shoulder Strike / Lean

- Direction: Body-weight force through the shoulder.

- Feeling: Heavy, pressing force that moves through the whole body.

- Application:

- Used to knock an opponent off balance in close-quarters situations.

- Can also be used as a defensive movement by absorbing force.

- Example: If an opponent grabs your arm, you can step in and use your shoulder to push them away.

- Example in Forms: Seen in "Shoulder Stroke" after "Grasp the Bird’s Tail."

How the Eight Energies Work Together ?

The Eight Energies are not isolated techniques but rather fluid transitions between movements. Here’s how they interact:

-

Peng → Lu → Ji → An:

- Ward Off (Peng) to create a structure.

- Roll Back (Lu) to absorb force.

- Press (Ji) to counterattack.

- Push (An) to finish the movement.

-

Cai → Lie → Zhou → Kao:

- Pluck (Cai) to pull an opponent off balance.

- Split (Lie) to separate their force.

- Elbow (Zhou) for a short-range attack.

- Shoulder (Kao) to finish with full-body power.

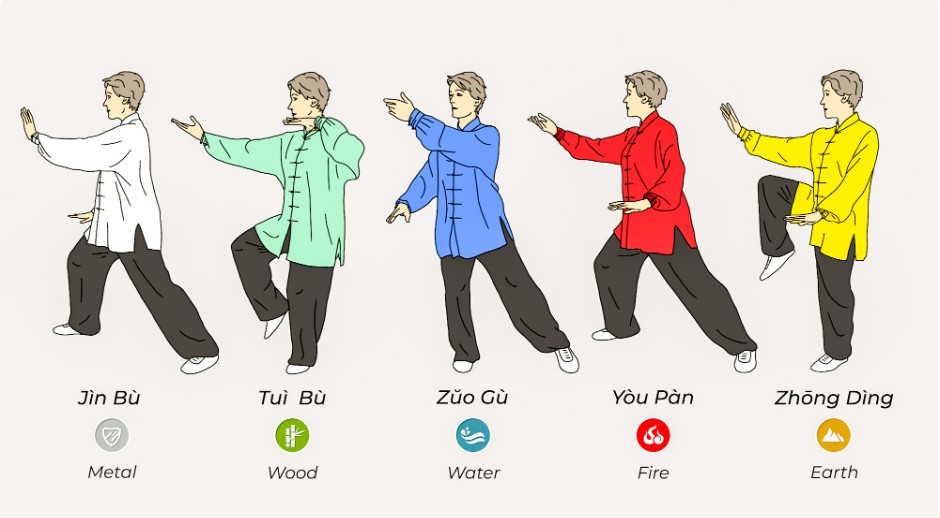

2. The Five Steps (Wǔ Bù / 五步) – Footwork and Directional Movement

The Five Steps (五步 / Wǔ Bù) form the footwork principles of Tai Chi, complementing the Eight Energies (八法 / Bā Fǎ). These steps represent different ways of moving, positioning, and shifting weight, ensuring balance, agility, and control.

The Five Steps are:

- Advance (進步 / Jìn Bù) – Moving forward

- Retreat (退步 / Tuì Bù) – Moving backward

- Look Left (左顧 / Zuǒ Gù) – Moving or turning left

- Look Right (右盼 / Yòu Pàn) – Moving or turning right

- Central Equilibrium (中定 / Zhōng Dìng) – Maintaining balance in the center

These steps are not just physical movements but also strategic concepts in Tai Chi’s martial applications.

1. Advance (進步 / Jìn Bù) – Moving Forward

- Meaning: Moving forward with balance and intent.

- Principle: Expanding force while maintaining stability.

- Application in Combat:

- Used to close distance and apply pressure to an opponent.

- Often follows Ji (Press) or An (Push) to drive an opponent backward.

- Example: In "Step Forward to Deflect, Parry, and Punch," the step forward adds momentum to the strike.

- Training:

- Practice stepping forward smoothly and rooted (without overextending).

- Coordinate breathing with each step—inhale to prepare, exhale to step.

2. Retreat (退步 / Tuì Bù) – Moving Backward

- Meaning: Moving backward while maintaining balance and control.

- Principle: Yielding and neutralizing force rather than resisting directly.

- Application in Combat:

- Used to escape attacks or reposition strategically.

- Works with Lu (Roll Back) to absorb and redirect an opponent’s force.

- Example: In "Step Back and Repulse Monkey," retreating creates space while deflecting an attack.

- Training:

- Avoid collapsing the posture while stepping back—stay upright and controlled.

- Coordinate weight shifting so the back foot is planted before lifting the front foot.

3. Look Left (左顧 / Zuǒ Gù) – Moving or Turning Left

- Meaning: Moving or adjusting focus to the left.

- Principle: Awareness of lateral movements and defense.

- Application in Combat:

- Used to redirect an attack to the left or strike from an angle.

- Works with Lie (Split) to create an opening.

- Example: In "Single Whip," the leftward shift redirects force while maintaining balance.

- Training:

- Focus on whole-body turning—the waist, not just the arms, leads the movement.

- Keep the eyes engaged—turn the head before shifting the body.

4. Look Right (右盼 / Yòu Pàn) – Moving or Turning Right

- Meaning: Moving or adjusting focus to the right.

- Principle: Ensuring agility and adaptability to different angles.

- Application in Combat:

- Used to evade attacks or reposition offensively.

- Works with Zhou (Elbow) for close-range counters.

- Example: In "Fair Lady Works at Shuttles," the rightward movement sets up diagonal attacks.

- Training:

- Synchronize stepping and turning—don’t twist the body without shifting the feet.

- Maintain an upright posture—avoid over-leaning in any direction.

5. Central Equilibrium (中定 / Zhōng Dìng) – Maintaining Balance in the Center

- Meaning: Staying balanced, rooted, and ready for movement in any direction.

- Principle: Stability and control over weight distribution.

- Application in Combat:

- Ensures readiness to respond to attacks or changes in positioning.

- Works with Peng (Ward Off) to maintain structural integrity.

- Example: In Tai Chi stance practice, the body remains stable and responsive.

- Training:

- Stand in Tai Chi stance, focus on weight evenly distributed.

- Practice weight shifting smoothly from one leg to another without losing balance.

How the Five Steps Work Together ?

The Five Steps are the foundation of Tai Chi footwork, ensuring that movements are fluid, efficient, and controlled. They are often paired with the Eight Energies:

- Peng (Ward Off) + Jìn Bù (Advance) → Expanding forward with structural integrity.

- Lu (Roll Back) + Tuì Bù (Retreat) → Yielding and redirecting force backward.

- Lie (Split) + Zuǒ Gù (Look Left) or Yòu Pàn (Look Right) → Angling off an opponent’s centerline.

- An (Push) + Zhōng Dìng (Central Equilibrium) → Maintaining balance before issuing force.

Together, these movements create the core strategies of Tai Chi:

- Advancing and retreating wisely instead of rushing or hesitating.

- Using angles and turning to avoid direct force.

- Maintaining central stability for strength and adaptability.

Together, these Thirteen Postures form the core principles behind all Tai Chi movements, regardless of style (Yang, Chen, Wu, etc.). They are essential for developing structure, internal energy, and martial applications in Tai Chi practice.